Shelley's

Ashes

Copyright 2008/2013

by John Lauritsen

According to Greek legend, the ashes of Achilles and Patroklos were mingled in a golden urn; they were buried together in a common tomb. *

Alan Bray begins his book The Friend by describing a 17th century tomb in the chapel of Christ's College, Cambridge, in which two men were buried together, Sir John Finch and Sir Thomas Baines. These men met as students at Christ's College, and formed a friendship which lasted for the rest of their lives. One of them, John Finch, described their friendship as an “Animorum Connubium”: a marriage of souls.

Bray recounts many other pairs of loving friends who were buried together in a common tomb. For example, a tomb was found in Istanbul for two English Knights: Sir John Clanvowe and Sir William Neville, who both died in October 1391. According to a chronicle compiled by the monks of Westminster Abbey:

In a village near Constantinople in Greece the life of Sir John

Clanvowe, a distinguished knight, came to its close, causing to his

companion on the march, Sir William Neville, for whom his love was no

less than for himself, such inconsolable sorrow that he never

took food again and two days afterward breathed his last, greatly

mourned, in the same village. These two knights were men of high repute

among the English, gentlemen of mettle and descended from illustrious

families. (translation from the Latin by Alan Bray, The

Friend,

p.

19)

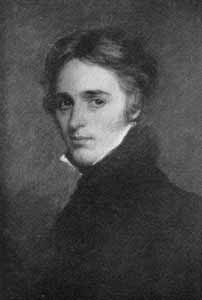

Percy Bysshe Shelley painted by William Edward West.

Edward Ellerker Williams painted by George Clint.

In the Protestant Cemetery in Rome are buried the ashes of Percy Bysshe Shelley, mixed with the ashes of his beloved friend, Edward Ellerker Williams. The two friends died together in a boating accident in the Gulf of Spezia on 8 July 1822; both were only 29 years of age. Next to their grave is a tombstone, on which is inscribed an epitaph which Shelley had composed for himself and Williams:

These are two friends

whose lives were undivided.

So let their memory be now they have glided

Under the grave: let not their bones be parted

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

So let their memory be now they have glided

Under the grave: let not their bones be parted

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

Now, this is not quite the account you will read in the standard Shelley biographies, so I'll need to explain. This little essay will be an exercise in thinking things through, in making the appropriate connections. In the vernacular, I'll be “connecting the dots” — dots that were always there, right before the eyes of the biographers.

When I first read this epitaph many years ago, I sensed it was gay. Here is the standard version:

EPITAPH

These are two friends whose lives were undivided;

So let their memory be, now they have glided

Under the grave; let not their bones be parted

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

(Shelley/Hutchinson 1970)

These are two friends whose lives were undivided;

So let their memory be, now they have glided

Under the grave; let not their bones be parted

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

(Shelley/Hutchinson 1970)

However, a strikingly different version is found in Thomas Medwin's The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley (London 1847). The salient differences are the addition of the verb mingle and the substitution of dust for bones:

EPITAPH

They were two friends, whose life was undivided.

So let them mingle. Sweetly they had glided

Under the grave. Let not their dust be parted,

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

(Medwin 1847/1913, vol. II, p. 390)

They were two friends, whose life was undivided.

So let them mingle. Sweetly they had glided

Under the grave. Let not their dust be parted,

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

(Medwin 1847/1913, vol. II, p. 390)

Medwin knew that Shelley and Williams had been cremated, and therefore used “dust” rather than “bones”. (“Dust” had to be used, rather than “ashes”, for the line to scan.) “Mingle” in Medwin's version is stronger and more erotic, suggesting that bodies of the two friends had mingled when alive.

H. Buxton Forman provides the following note to the above Medwin version of the Epitaph:

This version of the epitaph may perchance have been written by Shelley: probably more than one manuscript exists. the best version is that of the holograph in Mr. Bixley's Note Book No. I:These are two friends whose lives were undivided —

So let their memory be now they have glided

Under the grave, let not their bones be parted

For their two breasts in life were single-hearted.

The Medwin variant might be recorded in variorium editions of Shelley with a caution. Mary Shelley had the Note Book in question when she first published the epitaph in 1824; and, if that was her sole source, she must have misread breasts for hearts, which scarcely makes sense, although it has satisfied editors and critics so far. Although written in pencil, the words are all absolutely unmistakable. (Medwin 1913)As Forman points out, the final line makes no sense when “two hearts” is substituted for “two breasts”. However, Mary Shelley may not simply have “misread breasts for hearts”, but deliberately altered the line to camouflage its physicality. She did her best to censor homoeroticism in Shelley's works — for example, her unforgivable suppression and then bowdlerization of Shelley's masterful translation of Plato's dialogue on Eros, The Banquet (or Symposium), which was only published complete and unbowdlerized more than a century after Shelley finished it.

Medwin was a cousin and life-long friend of Shelley's. Like the other men in the Shelley-Byron circle, he was gay — or, as it were, bisexual. (All of these men were married and had children.) Medwin informs us through his Life that Shelley wrote the epitaph for himself and Edward Williams.

Edward John Trelawny tells how Shelley and Williams died, and how they were cremated and buried. The bodies of Shelley and Williams were found, washed up on the Italian shore. Trelawny took charge, and had them buried in temporary graves. He had a portable furnace made. Byron and Trelawny then had the bodies exhumed and burned to ashes, as they performed pagan rites:

[Cremation of

Williams] As soon as

the flames became clear, and allowed

us to approach, we threw frankincense and salt into the furnace, and

poured a flask of wine and oil over the body. The Greek oration was

omitted, for we had lost our Hellenic bard. It was now so insufferably

hot that the officers and soldiers were all seeking shade. (Trelawny p.

90)

Similar rites were performed the next day as Shelley was cremated. The ashes were put in boxes and carried aboard Byron's yacht. Leigh Hunt was also present at the cremation of Shelley, but was too upset to watch it, and retired to the coach. Medwin joined the group, arriving a few hours too late to take part in the cremation.

Trelawny sent a box of ashes to Rome. When he arrived there the next year, he purchased two adjacent lots, one for Shelley and one for himself. He had a tombstone put up, with three lines from The Tempest:

Nothing of him that

doth fade

But doth suffer a sea change

Into something rich and strange.

But doth suffer a sea change

Into something rich and strange.

A box of ashes was given to Williams's common-law widow, Jane.

Now, I pose the question: Were the ashes of Shelley and Williams mixed or were they kept separate? Let's examine what we know.

First and foremost, Shelley and Williams loved each other. Trelawny in his Recollections says directly that Shelley loved Williams, that Williams loved Shelley, and that he loved both of them. The epitaph is an expression of love that goes far beyond mere friendship. The mutual love of Shelley and Williams was known and acknowledged by the men in their circle, who treated them as a couple.

The epitaph was known to Medwin and Trelawny, and presumably also to Byron. Here's the situation: they are mourning the deaths of their friends, whom they have cremated, using a pagan ritual with Greek allusions (suggesting Greek Love). They know that their friends had desired to be buried together. Aboard Byron's yacht they are alone with the ashes. No outsiders are present. Now, what do they do?

Yes, they mix the ashes together! Trelawny would not have balked: he had the audacity and the imagination.

Decades passed. Trelawny lived into a vigorous old age. When he finally died — on 13 August 1881, at the age of 89 — his plans had been laid well in advance. His body was embalmed and sent to Germany to be cremated. His mistress, Emma Taylor, then took the ashes to Rome, where they were buried in the lot he had purchased in 1823, next to Shelley's grave. At his request, the four lines of Shelley's epitaph were carved on his tombstone:

These are two friends whose

lives were

undivided.

So let their memory be now they have glided

Under the grave: let not their bones be parted

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

So let their memory be now they have glided

Under the grave: let not their bones be parted

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

Although biographers have assumed that Trelawny meant Shelley and himself as the “two friends”, this makes no sense. Trelawny had known Shelley for only half a year. As much as Trelawny loved and admired him, he could hardly have described his life and Shelley's as “undivided”. And besides, he knew that his own ashes would be alone. The epitaph on the tombstone was not an act of presumption, but of loyalty — it did not refer to Trelawny at all, but to Shelley and Williams, the two friends whose mingled ashes lie in the adjacent grave.

# # #

Trelawny painted by William Edward West

in 1822.

Trelawny in his eighties — still handsome.

Trelawny in his eighties — still handsome.

Afterword

Now, the reader may wish to go back through this essay, to decide where and how much I have engaged in speculation. There's nothing wrong with speculation per se; in science it's known as formulating hypotheses. However, a writer should make clear the basis of his conclusions; it should be apparent when he is speculating and when he is using facts that are established beyond reasonable doubt.

Trelawny did have the motive and the opportunity to mix the ashes, and it was in his character to do so. Indeed, it's unthinkable he would not have. Although the surviving men in the Shelley-Byron circle kept the secret well, Medwin and Trelawny at least hinted at it.

What happened to the other box, the one that was given to Jane Williams? Well, after the death of Edward she returned to England, where she became the common-law wife of Shelley's old friend, Thomas Jefferson Hogg. Although they never married legally, the partnership was a happy one; they had one daughter, Prudentia, and Hogg was a good stepfather to her children by Edward Williams. Jane Williams-Hogg outlived him, dying in 1884 at the age of 86. She was buried next to Hogg in Kensall Green cemetery; in her coffin was a box containing ... the mixed ashes of Williams and Shelley. And so at last they were all re-united: Shelley with his two best friends, and Jane with her two common-law husbands. Hogg would have liked Williams, and Williams would have liked the man who raised his children. And Shelley and Jane were the best of friends.

References

Alan Bray (2003). The Friend. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

H.J. Massingham (1930). The Friend of Shelley: A Memoir of Edward John Trelawny. New York: Appleton and Co.

Thomas Medwin (1913). The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley (H.B. Forman, Ed.). London: Humphrey Milford. [Expanded edition of original work published in 1847.]

Scott, Winifred. (1951). Jefferson Hogg: Shelley's Biographer. London: Jonathan Cape.

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1970). Poetical Works, edited by Thomas Hutchinson; a new edition, corrected by G.M. Matthews. London: Oxford UP.

Plato. (2001). The Banquet. (P.B. Shelley, Translator, J. Lauritsen, Editor and Foreword) Provincetown: Pagan Press.

William St. Clair (1977). Trelawny: The Incurable Romancer. New York: The Vanguard Press.

Edward John Trelawny (1858). Recollections of Shelley and Byron. London: Moxon. Repr. 2000 with Introduction by David Crane, New York: Carroll & Graf, 2000.

Notes

* In the Iliad, the ghost of Patroklos visits Achilles, pleading that his body be cremated and his ashes placed in the same golden urn with his. To read this excerpt, as translated by Edward Carpenter, click here.

** Two lines from “Passages of the poem, or connected therewith”, which were not printed with Epipsychidion.